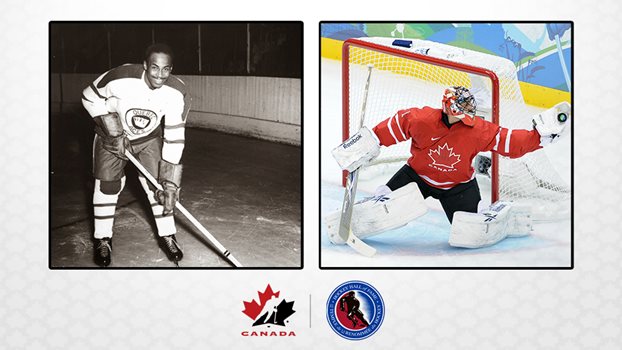

Dynamic duo headed to the Hall

Roberto Luongo and Herb Carnegie join four others in Class of 2022 for Hockey Hall of Fame

Two standout Canadians will be represented when the Class of 2022 goes into the Hockey Hall of Fame this fall.

Of the six names announced Monday, two have connections to Hockey Canada—legendary netminder Roberto Luongo will be enshrined in the player category, while Herb Carnegie will go in as a builder.

A closer look at the inductees…

Few goaltenders can match the international résumé of Roberto Luongo, who played 34 games across 10 events spanning 17 seasons, from the 1998 IIHF World Junior Championship to the 2014 Olympic Winter Games.

After earning Top Goaltender and Media All-Star Team honours at the 1999 World Juniors in Winnipeg, backstopping Canada to a silver medal, Luongo played in four IIHF World Championships in a five-year span from 2001-05, winning back-to-back gold medals in 2003 and 2004. Overall, only Sean Burke and Cam Ward have spent more time in the Canadian net at worlds than Luongo (856 minutes played).

In addition to his place on Canada’s championship-winning entry at the 2004 World Cup of Hockey, the Montreal product was also part of three Canadian contingents at the Olympic Winter Games, most notably at the 2010 Games in Vancouver when he capped his tournament with a 34-save effort in the gold medal game win over the U.S.

Honoured posthumously, Herb Carnegie is revered as one of the best players of his time and a pioneer for Black players in Canada. Carnegie battled racism and discrimination throughout his entire playing career, with many holding the view that he was kept out of the NHL simply because he was Black.

The Toronto-born forward was a standout in the Ontario and Quebec semi-professional leagues, earning three consecutive Quebec Senior Hockey League MVP awards from 1947-49. He joined the Quebec Aces in 1949-50 where he mentored another Canadian legend, Jean Béliveau—together winning the league championship in 1953. After retirement in 1954, he became a successful investor and founded one of Canada’s first hockey schools, the Future Aces, in 1955.

Carnegie’s family and friends had rallied together to get him into the Hockey Hall of Fame. They worked with the Hockey Diversity Alliance and created a petition to get him inducted in the Builder category to recognize his historic career that influenced generations of Black hockey players. Carnegie was also inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 2001 and the Ontario Sports Hall of Fame in 2014.

The duo will officially be inducted on Nov. 14 at the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto, joined by fellow inductees Daniel and Henrik Sedin, Daniel Alfredsson and Riikka Sallinen.

For more information: |

- <

- >